When GE 2020 candidates introduced themselves ahead of the election campaign, a fair number of them told us they grew up in HDB rental flats. Notably, a 55-year-old candidate mentioned that he grew up in an HDB rental flat at Toa Payoh in the 1960s and 70s, with rent of only “$4 a year”.

Well, Singapore has changed so much from the time when these candidates were young. Knowing what it’s like to be living in a rental flat right now (which, sadly, is often associated with being in chronic hardship or distress), we wondered if it was the same growing up in a rental flat back then.

So, we did a lot of research. Here’s 5 facts about HDB rental flats from the 1960s onwards that will make you question election candidates when they say: “I grew up in a rental flat.”

Fact #1: In the early 1960s, HDB started by providing ONLY rental flats

Established pre-independence in 1960, HDB’s primary objective was to provide affordable housing for the masses, not just for the poor.

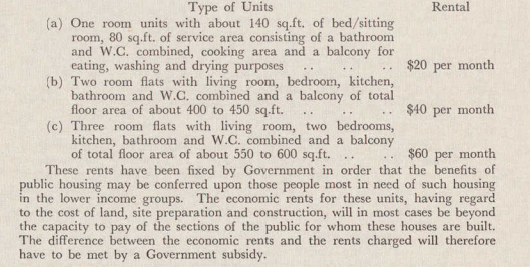

To achieve its objective, HDB had initially set out to provide affordable rental housing. According to its 1961 Annual Report, HDB started out by building more than 7,000 one-room, two-room and three-room flats in a 40-30-30 proportion. And these were the rents for such flats:

The cheapest rent was for one-bedroom flats, at $20 per month. In case you’re wondering, the MAS inflation calculator says that $20 in 1961 amount translates to roughly $88 today.

Fact #2: Rental flats served as much of the population as today’s BTO flats

Like BTO flats, rental flat applicants have always been subject to an income ceiling.

In the early days of HDB, a rental flat applicant’s monthly income must not exceed $500, whereas the family’s income must not exceed $800*. (A lower limit was set for one-room units with a family income ceiling of $250.)

How much of the population does such an income ceiling cover? Well, HDB’s 1963 Annual Report stated that the rental flats “will serve 75% of the working population in Singapore” whose monthly income ranged from $100 to $500.

Compare this to the target demographic of HDB’s Build-To-Order (BTO) flats today. According to a 2019 Singapore Business Review article citing DBS Equity Research, an “estimated 75% of Singapore households” fall under the current $14,000 income ceiling that allows them to apply for BTO flats and qualify for housing grants.

Who knew that, financially-speaking, early rental flats were more similar to BTO flats of today than rental flats?

*A $800 income in 1965 equals $3,136 in 2019 terms. The current income ceiling for rental flats is $1,500.

Fact #3: Demand for rental flats remained high despite home ownership push

After relieving the acute housing shortage of the early 1960s, HDB launched the ‘Home Ownership for the People’ scheme in 1964. A first batch of 2,068 flats was launched for sale in Queenstown.

The purpose of the scheme, according to the Annual Report that year, was to “encourage a property-owning democracy in Singapore, and to enable Singapore citizens in the lower-middle income group to own their own homes.”

By the end of the year, there were over 1,600 takers for the Queenstown flats, which were sold with 99-year leases at $4,900 for a two-room flat and $6,200 for a three-room flat. The income ceiling was set at $800 (individual) and $1,000 (total family income)—not that much different from rental flats.

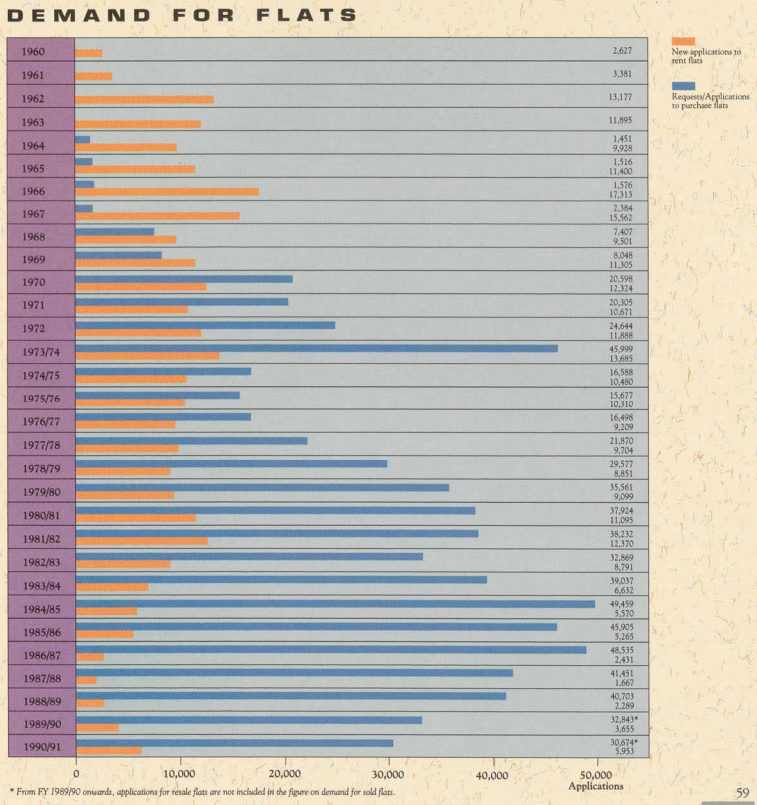

HDB rolled out the home ownership scheme to other estates in 1965. However, applications for rental flats continued to exceed that of sold flats.

One of the key obstacles to persuading Singaporeans to buy flats, according to old newspaper reports, was saving up the $900 or $1,200 downpayment required for a two- and three-room flat respectively.

To address this, the government introduced the Public Housing Scheme in 1968, which allowed Singaporeans to pay for the costs of their HDB flats using their CPF savings instead of having to use their take-home pay.

In 1970, applications for sold flats exceeded that of rental flats for the first time. About 7,500 owners used their CPF savings to help pay for their flats, according to a June 1970 article in The Straits Times.

Fact #4: Rental flats were an “upgrade” for most

Nobody would view living in an HDB rental flat as an upgrade now, but in the 1970s and 1980s when Singapore’s massive resettlement programme was in full swing, many found their new rental flats to be a step up from living in a kampung.

Singaporeans who moved into new rental flats often had nothing but praise about their new surroundings, according to old newspaper reports.

For most of them, it was the first time they had water at the turn of a tap, electricity at the flick of a switch, and a proper flush toilet connected to a sewage system.

There were complaints, of course. Inconsiderate neighbours, a lack of privacy and rules such as not being allowed to keep pets or decorate the exterior of the home were common gripes.

Certain design aspects were also singled out for criticism, such as the dark corridors that featured in some HDB blocks.

In a parliament session in 1977, former Minister of State for Culture Andrew Fong warned about overcrowding in one-room flats, for households that have presumably overgrown their flats and need resettling into larger units.

The Minister had earlier cautioned that one-room flats would “degenerate into slums” if HDB did not take action.

Fact #5: Income for 3-room flat buyers and renters were about the same

Heading into the 1980s, the campaign encouraging Singaporeans to own their HDB flats resulted in applications to buy that surpassed 35,000 a year. However, there was a persistent number of applicants, about 9,000 a year, who would apply to rent.

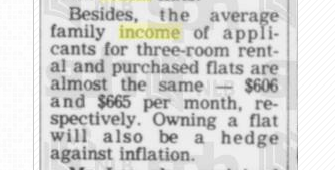

It’s not just low-income families who rented flats instead of buying them; a September 1982 article in The Straits Times pointed out that there was little difference between the average family income between rental and purchase applicants for three-room flats at the time.

In that month, once and for all, HDB closed the three-room rental register; Singaporeans who wanted to live in three-room flats (which make up about 30% of applicants at the time) had no choice but to buy them.

To not leave those unable to afford a flat stranded, HDB simultaneously raised the rental income ceiling for one- and two-room flats from $500 to $800—the previous ceiling for three-room flats.

HDB also decided to stop building new flats for rent and focus on building flats for sale.

Only with these actions did the demand for rental flats begin to decline. In 1983, 30% of flats were rental flats. In 1990, this was cut down to 13% as HDB progressively demolished rental flats, converted three-room rental flats to sold units, and sold flats to sitting tenants at a discount.

So, in seven years, the rental flat stock was reduced drastically from 133,445 to 81,184 units. Over time, this was further reduced to 42,800 units in 2008 (5% of total units) before the government saw the need to build new rental flats once more.

Today, roughly 63,000 rental flats make up about 6% of total HDB dwelling units.

HDB Sold Flats vs Rental Flats – Selected Years

| Year | Sold Flats | Rental Flats | Total Flats | % of Rental Flats vs Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | 2,884 | 51,546 | 54,430 | 94.7% |

| 1970 | 31,154 | 89,515 | 120,669 | 74.2% |

| 1976 | 120,340 | 122,839 | 243,179 | 50.5% |

| 1983 | 311,371 | 133,445 | 444,816 | 30.0% |

| 1988 | 499,860 | 117,614 | 617,474 | 19.0% |

| 1994 | 612,530 | 68,386 | 680,916 | 10.0% |

| 2007 | 838,488 | 46,652 | 885,140 | 5.3% |

| 2018 | 999,468 | 62,882 | 1,062,350 | 5.9% |

Source: HDB, 99.co

The rental flats we know today

The point of this article is to show that families and households living HDB rental flats today are doing so under very different—and possibly far more challenging—circumstances than that of rental flat residents in the 60s, 70s and 80s.

Sure, there can be overlaps and life could’ve been tough as well. But the entire dynamic of a rental flat versus sold flat back then was different. The entire social dynamic was different. The economy was different. Cost of living was different.

In 2020, many of the 52,000 out of 1,040,000 HDB households currently living in rental flats are doing so not by choice, but by necessity. They earn a household income of no more than $1,500, many far lower than that.

Some are in desperate need of a rental flat for a roof over their heads, but are denied due to regulations.

What is also worrying is that more than half of rental flat applicants used to own flats, but somehow lost them. These aren’t your kampung resettlers of yesteryear.

Talk is, ultimately, cheap. To understand the plight of Singaporeans grappling with life in the lower echelons of society right now, sincere candidates running for election can do much better than saying “I grew up in a rental flat.“

[For more information on renting a flat from HDB, visit the Public Rental Scheme page.]

[To volunteer to help residents living in rental flats, join Project Homeworks or visit Giving.sg for a list of activities.]

If you liked this article, 99.co recommends Buying a HDB flat as a single parent in 2020: How to do it and $1,500 is not a Fixed Income Ceiling for Rental Flats

Looking for a property? Find your dream home on Singapore’s most intelligent property portal 99.co.

The post 5 facts that make you question the “I grew up in a rental flat” election-speak appeared first on TinySG.

from TinySG https://tinysg.com/5-facts-that-make-you-question-the-i-grew-up-in-a-rental-flat-election-speak/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=5-facts-that-make-you-question-the-i-grew-up-in-a-rental-flat-election-speak

No comments:

Post a Comment